The fascinating history of the city of Matera

The history of Matera is rich in events and transformations that have shaped the city over time.

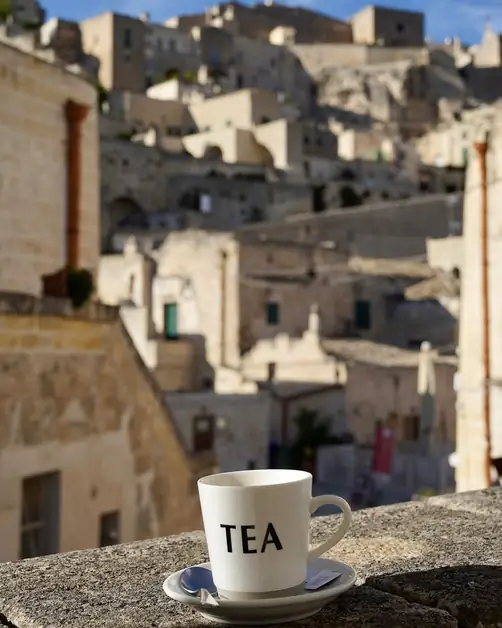

Matera leaves you speechless. You arrive, see carved walls. Steps, roofs turning into streets. You think, "This was a prehistoric city." Sounds cool, but tricky historically.

"City" isn't just "a place people lived." A city means size, organization, shared spaces. An ancient settlement could be temporary, scattered. People were there, left traces, but no urban center.

Matera teeters on this fascinating edge. People lived here early, city came later.

What makes a community a "city"

Historians see cities as complex organisms. Not just caves or huts. You need organization: water management, workspaces, markets, defenses. A big community, beyond a few families.

So, saying "Matera was prehistoric city" misleads. Yes, ancient humans were around. But "presence" isn't "city." Urban planning, administration make cities. Cities are processes, not dots on maps.

Want more insight? Check this story: the captivating history of Matera

.

Before the city: ancient traces in Murgia Materana

Matera has a long memory. Early memories live in caves. The Murgia Materana Park spans 8,000 hectares. Archaeologists found ancient remains here. Human presence dates back to Paleolithic. It's real, but not "city." It's adapting to nature.

Picture ancient logic: natural shelters, water sources, wind protection. No roads, no neighborhoods, no urban center. A mosaic of used, reused places.

The Grotta dei Pipistrelli is nearby. Not "Matera's first home," but it shows that lifestyle. Natural shelters, living with the rock.

Planning a nature-archaeology visit? Check this guide: explore Murgia Materana Park

.

Natural vs. artificial caves: a game-changer

In Matera, natural vs. artificial matters. Natural caves form slowly. Water shapes limestone, creating cavities. It's geology, not architecture.

Artificial caves are man-made. People designed the rock. They dug, expanded, connected. For Matera, this is crucial. Rock became building material, not just scenery.

Chronology matters here. Prehistory lacked metal tools for precise digging. Neolithic had huts, trenches, organization. But no widespread cave homes like the Sassi.

Matera's birth as a city: Early Middle Ages

The turning point comes in the Early Middle Ages. A stable, large community emerges. Documented, recognizable urban nucleus forms.

Before, the area was lived in. Natural caves, people, presence. But no organized urban settlement with lasting city functions.

This isn't just a small detail. It changes how you see Matera. It's not the "oldest city in the world" literally. It's a city built on ancient human ground. Over time, it structured and defended itself. It finally named itself.

La Civita: first heart between two ravines

To find where Matera "lights up," look at Civita. It's the highest point in the historic center. It sits on a rocky ridge, about 400 meters above sea level. This place feels like a natural center. It overlooks two ravines and controls passages. It ties the landscape together.

They found ancient artifacts here, from the metal age, around 3,000 years ago. This shows a long history of attention and presence. Matera clearly appears in records by the 8th century AD. This was during the Lombard rule in Southern Italy.

Then history speeds up. Matera falls into the Emirate of Bari's orbit. In 871, Emperor Ludovico II attacks, burning the city. It wasn't just a battle. It shows how strategic and contested the city was.

In later centuries, the city fortified itself. The first narrow wall is from the Norman era (around the 11th century). During the Angevin age, defenses expanded with towers and gates.

Sassi and Piano: a vertical city expanding over time

Between the two ravines below Civita, two districts appear. Sasso Caveoso and Sasso Barisano are famous. These rock settlements likely formed in the early Middle Ages. They consist of artificial caves. People adapted them into homes, shops, cisterns, and stables.

The functional layering is amazing. In the Sassi, there's no "ground floor." There are levels. Paths, stairs, and rock ledges connect spaces. These places sometimes stack like drawers. The Sasso Caveoso resembles an amphitheater, facing south. Sasso Barisano faces north. It later grows with buildings.

Then there's the Piano, the historic center's top part. It develops near Civita on a plateau. It descends towards the ravine. Here, during the Renaissance and Baroque, the city "dresses up." Medieval caves turn into houses and palaces. The urban layout becomes more "classic," with streets and squares.

A route shows this connection between parts. Start at Piazza Pascoli, follow Via Ridola, then Via del Corso to Piazza Vittorio Veneto. This path links Sasso Caveoso and Sasso Barisano into one urban system.

If you want a guided tour through the rock districts, start here: discover the Sassi of Matera and their unique charm

Field experience: the moment you understand Matera's "shape"

The first time I tried to "read" Matera as a city, I got lost. I wandered into the Sassi with no direction, like any neighborhood. After ten minutes, I was confused. I climbed up and down stairs. I ended up on terraces that felt like streets. Then on streets that led to doors. The only sound was my footsteps echoing. Sometimes the wind howled through the ravines like an empty channel.

I paused on a viewpoint and did something simple. I looked up. Then I understood. Above me was Civita, the city's "body." Further was the Piano with its stone volumes. On the sides, the Sassi spread along the slopes. I remembered the chronicler Eustachio Verricelli (late 16th century). He described Matera as a bird without a tail: Civita as the body, Piano the neck and head, Sassi the wings. It wasn't just a metaphor anymore. It was a mental map.

The mistake was trying to find a horizontal city in a vertical place. Here's a practical tip I learned: Before diving into the Sassi, take 5 minutes at a viewpoint. "Rebuild" the whole shape with your eyes. Then descend. You'll navigate better, tire less, and understand why "city" here means structure, not label.

Mistakes to avoid when narrating Matera's origin

The first mistake is common: confusing ancient habitation with ancient urbanization. Saying "people were here in the Paleolithic" is true. Saying "this was a city in the Paleolithic" is different.

The second mistake is flattening everything to the Sassi. As if Matera is "just" cave houses. Matera is a system: Civita, Sassi, Piano, Murgia, ravine. Remove one, and you lose how the city developed over time.

Third mistake: skipping the difference between natural and artificial caves. It seems technical, but it's crucial. It shows when humans moved from "living in rock" to "designing rock." In Matera, this marks the start of a real urban settlement.

Finally, a practical mistake (and also a narrative one): describing Matera as flat. Without levels, ravines, and connecting paths, it's confusing. Matera is a city understood with your legs, but first with a good mental map.

Matera isn't "prehistoric" in urban terms. It's more interesting. It's a city born when social and technical conditions allowed. It sits on land known to humans for ages. Here, history isn't a date. It's a way of seeing: distinguishing presence from structure, shelters from neighborhoods, natural rock from architecture.